The Civil War Divides Methodists

A much greater discussion, however, was occasioned by the report of the Committee on Episcopacy, which was given on May 21st. Bishop James O. Andrew, a "modest quiet man, who had never felt quite at home in his elevated position," had, by indirection, become a slave owner. An elderly lady of Augusta, Georgia, had left a slave girl to Andrew on condition that he should free her and send her to Liberia when the girl reached the required age. The girl refused to go to Liberia, and legally she remained the property of the Bishop. He also had inherited a young male slave from his first wife, and on his second marriage he married a lady who had inherited slaves from her first husband. Under the laws of the state of Georgia he was prohibited from setting free these slaves. When the good Bishop reached Baltimore on his way to the Conference, he learned that his affairs were the major subject of conversation among delegates and surely would be introduced and debated at the conference. This debate continued for eleven days and filled almost one hundred pages of the official record of the conference. Delegates were loath to take drastic action against Andrew, only "affectionately requesting" that he resign, or "desist from the exercise of this office so long as the impediment remains."

Positions taken by Southern and Northern delegates clearly indicate the divergent views of the two sections of the country. Southern delegates took the position that the episcopacy was a co-ordinate body with the General Conference, and therefore, the conference had no constitutional right to suspend a bishop. They argued that Bishop Andrew had violated no rule of the church, inasmuch as a resolution had been passed in 1840 legalizing slaveholding in all grades of the ministry.

Northern delegates could not, of course, accept this argument. They held that a bishop was simply an officer of the General conference, and was amenable to it in every respect. The debates raged, the bishops tried mightily to effect a compromise, and it even was suggested that the issue be postponed to the next converence in 1848. Finally, however, on June 1st the question of virtual suspension of Bishop Andrew came to a vote and was carried by an affirmative vote of 111 to 66. The church with this vote, had come to a parting of the ways.

A committee of nine was appointed to devise an equitable method of dividing the church. On June 7th the committee issued its report, which came to be known as the "Plan of Separation." One June 8th, the Conference delegates, by an overwhelming majority of both Southern and Northern delegates, voted to adopt the Plan of Separation. Three days later the conference adjourned.

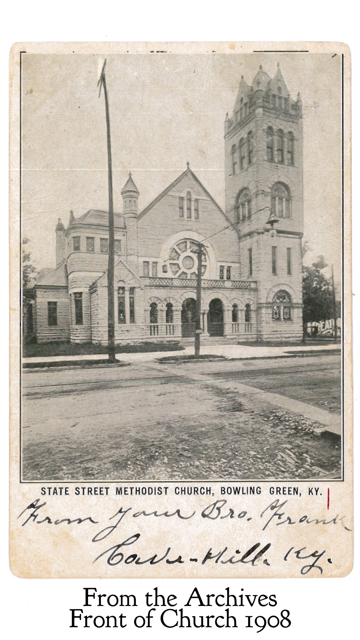

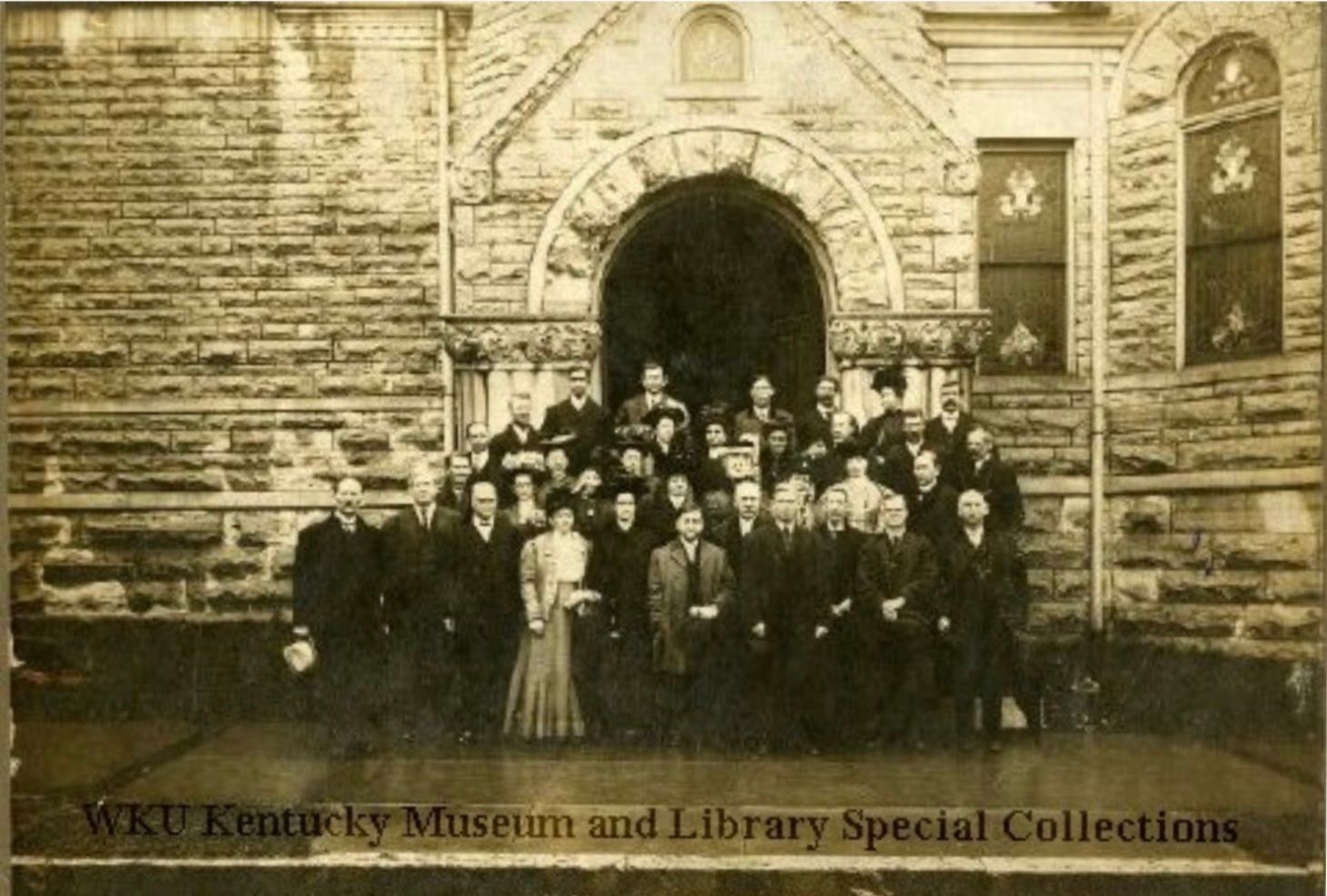

On June 12th the Southern delegates met in New York City and approved a statement to the members of the Southern Conferences, explaning what actions had taken place at the General conference and suggesting that a convention be called to meet in Louisville, Kentucky on May 11 1845. The Southern Conferences, with almost total unanimity, agreed to the calling of a conference, and it convened at the appointed time. On May 15th the Committee on Organization made its report. This report included a declaration of independence of the southern portion of the church from the jurisdiction of the General Conference. The report stated that it was "right, expedient, and necessary to erect the Annual Conferences represented in this convention into a disctinct ecclestial connection." It also expressed the desire to maintain "Christian union and fraternal relations" with their Northern brethren, and invited Bishops Soule and Andrews to become their bishops. On June 17, 1845, the report was adopted by a vote of 95 to 2, and the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, became a reality. The conflicting sentiments which had resulted in the vision of the church at the General Conference was mirrored in the local church and in the town of Bowling Green itself. Those whose sympathies lay with the South formed the State Street Methodist Episcopal Church, South. Members loyal to the Northern viewpoint assumed the name First Methodist Church. The latter congregation later changed its name to Kerr Memorial Methodist Episcopal Church, the name having been slected to honor the Reverend Mr. Daniel F. Kerr.

This division left Bowling Green Methodism in two small and substantially weakened congregations and seriously retarded religious growth. The State Street church was hampered by a succession of thirteen ministers in as many years. Also, the growing friction between North and South, and the increasing fear of armed conflict, created an atmosphere which was not conducive to the progess of the congregation.

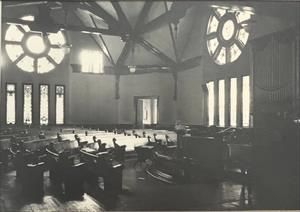

The spring of 1861 brought the outbreak of hostilities. The War presented a particularly difficult challenge for Methodists in Bowling Green. Sentiments were strong, and almost evenly divided between the warring factions. Church congregations, even families, were torn asunder, and deprivations which resulted from the war added physical hardships to the emotional suffering which the town's residents experienced. Bowling Green was strategically located almost midway between the larger cities of Louisville and Nashville, at the head of navigation of the Barren River, and on the main line of the newly completed Louisville and Nashville railroad. It was almost inevitable that Bowling Green would be invaded and occupied by either the Confederate or Union forces, and Confederate troops under the command of General Albert Sidney Johnston arrived in the town in the winter of 1862. The State Street church was converted into a hospital, and was so used during the entire period of occupation. With no church building in which to hold services, and with no minister to lead them, members of the congregation drifted apart, some worshipping with other denominations, many abandoning formal religious practices altogether. The situation did not improve when the military forces were withdrawn in the Spring of 1862. There was a scattered and dishearted membership, no minister, and a building scarcely fit to be used.

The church was rescued in 1863 by the arrival of the Reverend Mr. E.W. Bottomley, the congregation's forty-second minister in forty-three years. Bottomley, a man of zeal and determination, immediately set to work rebuilding the congregation. Looking at the scarred shell of the building, he decided that first priority must go to physical reconstruction. Under his leadership the building was repaired and placed in fine order. The minister turned his efforts next to rebuilding the membership. Working unceasingly, Bottomley soon had returned almost all of the congregation to the fold. The members renewed their vows at the altar, reconsecrated themselves, and once more assumed the work of the Master. The result of Reverend Bottomley's efforts was a great revival which attracted almost the entire population of the town.